Runner-up in the 2022 Student Blog Writing Competition

The Government’s menu regarding how they intend to address food insecurity in New Zealand is entirely different from the food (policies) it serves up. When the New Zealand Government agreed to enter the sustainable development goals in 2015, it embraced the challenge of eradicating food insecurity in New Zealand by 2030 (Charlton, 2016). So, as we approach the halfway mark, how are we tracking? The percentage of New Zealanders that face food insecurity has increased from 10% in 2014 to 14% in 2020 (Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, 2022). Māori and Pasifika are still overrepresented in those numbers (Ministry of Health, 2019). To put it simply, the problem of food insecurity in New Zealand is growing, not shrinking. So, what is the Government doing to combat it? Same old.

It is hard to fathom, with all the progressive developments in how aid is administered, (for example, Auckland City Missions (2019) program that focuses on preserving the dignity of recipients), how an antiquated system like ‘food for schools’ is still being utilized. School food programs have been in New Zealand on and off since 1937, with little evidence supporting its ability to substantially reduce food insecurity rates. A definition of insanity attributed to many authors, is the repetition of the same action and expecting a different result. So, does this Government’s persistence in applying a historically ineffective system to change the trajectory of food insecurity rates render it insane? Perhaps not insane, more likely intentionally ignorant and incompetent.

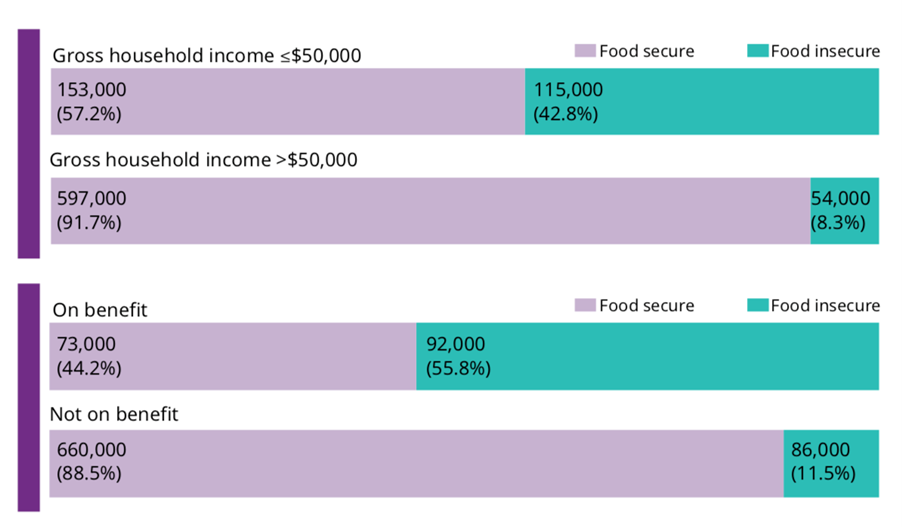

So why in 2022 is Labour still whipping the dead horse that is ‘food for schools’ to address insecurity rates? Because it is just enough. It is just enough of an effort so that Labour is seen to be making a ‘honest attempt’ without having to address the big picture, that being, food insecurity is a symptom, not the disease itself. The disease is the economic environment that racially segregates society, forming an unspoken class system. This class system puts a disproportionate number of Maori and Pasifika at risk of facing food insecurity due to not meeting the suggested income needed to reduce exposure to food insecurity. The suggested income required to reduce food insecurity is 50k p/a (Ministry of Health, 2019). Addressing New Zealand’s unspoken racial hierarchy and questioning the egalitarian cultural narrative would be political suicide; the safer option is to view food insecurity as a stand-alone issue, one in which in the Government, in true saviour style, can swoop in, feeding the mouths of hungry children and confirming the Labour Party is ‘there for them.’

Source: Ministry of Health.

That’s the menu. The food is that the Labour Party has little interest in making the bold social and economic changes needed to achieve substantial progress towards closing economic and health related gaps that racially segregate us. Addressing the root of the issue, subsidising families that fall below the 50K per annum mark would be difficult and costly, while most likely aggravating middle class New Zealanders who might see it as a handout scheme. That would also lose voters. So instead, they opt for the ‘just enough’ approach through the implementation of ‘schools for lunch’ (Ministry of Education, 2022). Once again, another token effort from a party that offers solutions to all problems through a white privilege lens. Instead of empowering parents of food insecure children with access to resources so that they can purchase nutritious food, they offer conditional support where the children are reliant on authority figures from the government and schools to supply them with food. The implicit assumption here is not hard to decipher: Labour feels that the families who face food insecurity issues do so because they are fiscally irresponsible. Therefore, they are untrustworthy of using food aid subsidies to purchase nutritious food for their families; it would probably all just go on booze and cigarettes.

Source: Ministry of Education. Lunch in a prison tray.

Conditional policies like ‘food for schools’ enforce harmful narratives and stigmas that lead to beneficiaries masking their financial positions to save humiliation. The assumed consensus is that people who find themselves facing these issues do so because of some sort of functional deficiency (Graham, et al., 2018). The structure of the policies designed to assist those in need have a clear underlying message, that is, only expertly applied governmental aid with tight restrictions and conditions can help you, because you are incapable of being responsible for yourselves. This is the classic result of a dominant culture attempting to ‘fix’ another culture. White privilege at its finest.

To make significant progress in eradicating food insecurity, we need to stop viewing the members of society that need food security as being financially incompetent. We must lose the distrust and paranoia that, if given, the money for direct financial assistance would be spent irresponsibly. More importantly New Zealanders need to decide if food is a right or a privilege. Research from the Ministry of Health shows citizens earning under 50k per annum were 406% more likely to face food insecurity than those who earned more. It showed the demographics that fell into this ‘red zone’ were heavily represented by Māori, Pasifika, beneficiaries, and those working minimum wage jobs. If food security is a right that the government aims to ensure every citizen enjoys, it knows what to do. But in the current environment, food security is a privilege reserved for educated, working, middle-to-upper-class New Zealanders, and a pipe dream for the rest.

References:

Charlton, K. E. (2016). Food security, food systems and food sovereignty in the 21st century: A new paradigm required to meet Sustainable Development Goals.

Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (2022). Food insecurity rates. https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#country/156

Graham, R., Hodgetts, D., Stolte, O., & Chamberlain, K. (2018). Hiding in plain sight: experiences of food insecurity and rationing in New Zealand. Food, Culture & Society, 21(3), 384–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/15528014.2018.1451043

Household food insecurity among children : New Zealand heath survey : summary of findings. (2019). Ministry of Health.

Ministry of Education. (2022). Ka Ora, Ka Ako | healthy school lunches programme.

https://www.education.govt.nz/our-work/overall-strategies-and-policies/wellbeing-in-education/free-and-healthy-school-lunches/

Ministry of Education, (2022). Lunch in a prison tray. Image.

Shining the light on food insecurity in Aotearoa : Auckland City Mission’s call to action. (2019). Auckland City Mission.